A friend is reading my grief book — Grief: The Inside Story – a Guide to Surviving the Loss of a Loved One — not for herself so much because she is still happily and healthily married, but for those she knows who have had to deal with the death of a spouse or child.

I am impressed with her willingness to try to understand what others have to go through in dealing with such a horrendous loss. Most people don’t want to know. Not that I blame them — I would have preferred not knowing, would have preferred to continue believing I was immune to such wild emotions, would have preferred . . . well, I would have preferred a lot of things. Or rather, I would have preferred them back then. I’ve gotten so used to the way my life now is, I can no longer imagine a different life. I can barely remember, at times, what my life used to be.

My friend and I talked about the book for a few minutes, then, as people often do, she said, “I can’t even imagine . . .” And as I often do, I responded, “You can’t imagine it, so there’s no reason to even try. It truly is an unimaginable experience.”

I was going to offer further words of comfort by mentioning that she is still way to young to have to worry about being a widow. Even though I know people of all ages who have had to deal with the experience, the widows I’ve been meeting since my move here are usually much older, and had long years with their spouse. Not that the length of time with a spouse mitigates the pain, but it seems more . . . fitting? understandable? . . . than the death of a someone still in their middle years.

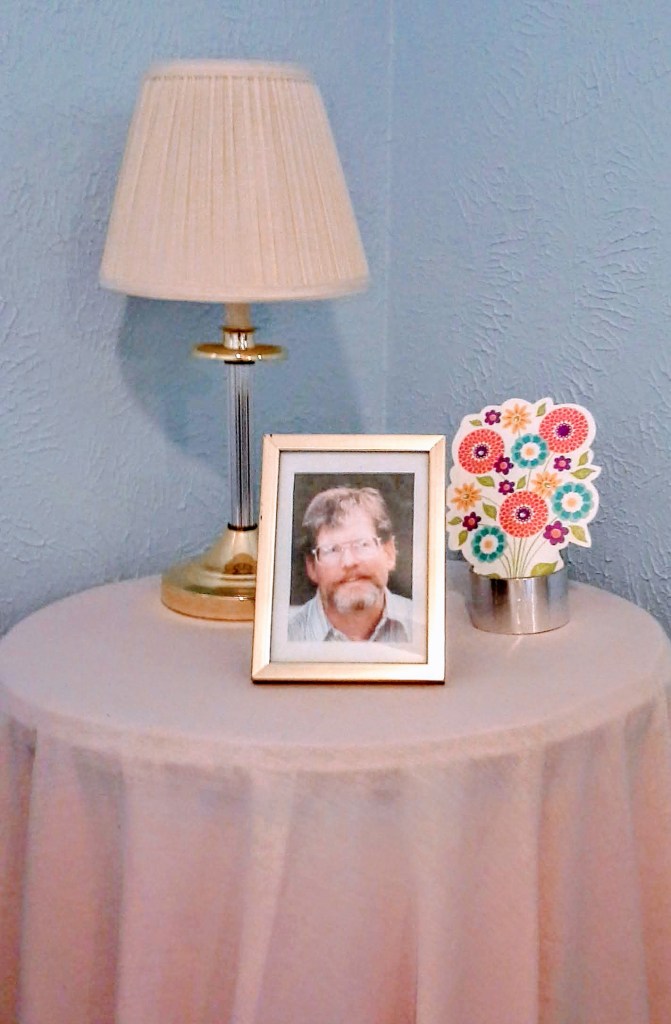

It wasn’t until much later that I realized this woman friend is only four years younger than I was when Jeff died. I tend to forget how relatively young I was (though I never forget how young Jeff was), probably because by the time I reared my head and looked around after all those dark years of pain and sorrow, I was way older.

I think it was my relative youth that made me so determined to live and thrive, not just survive, after Jeff’s death. Perhaps if I had been older, nearing my own expiration date, I might not have thrown myself into the whole grief experience but just . . . waited. Back then, I figured it was better to experience grief as it came rather than try to fight it off because I didn’t want to have to be dealing with the problems unlived and unresolved grief can cause in later years. (Buried grief can find its way to the surface through illness and emotional problems even decades later.) I wanted to be sure that I would be whole (except for that eternal void deep inside that still remains), that I would be able to experience to the full any happiness I could find. I also wanted to see where grief would take me.

Although I’m glad the pain and sorrow are gone (except for a residual sadness and nostalgia), I am grateful I gave myself over the experience. I never knew, couldn’t even have imagined that a person could experience such a depth of emotion, could experience something so . . . primal.

Now that I am through with that particular experience, I have no idea what I am going to do with my remaining years except continue to apply the lessons grief taught me, such as live each day the best I can, enjoy the good times, endure the bad, and be thankful for any blessings that come my way.

***

Pat Bertram is the author of Grief: The Inside Story – A Guide to Surviving the Loss of a Loved One. “Grief: The Inside Story is perfect and that is not hyperbole! It is exactly what folk who are grieving need to read.” –Leesa Healy, RN, GDAS GDAT, Emotional/Mental Health Therapist & Educator