Studies have indicated that happiness is found mainly in retrospect. For example, happy children don’t know they are happy. They simply are happy. It’s only later, when they look back, perhaps after a terrible time in their adult lives, that they realize they had been happy in their early years. For another example, when someone is involved in a challenging situation that takes all their time and energy, they don’t realize until later they were happy. In fact, often while going through this “happy” situation, people think they are decidedly unhappy.

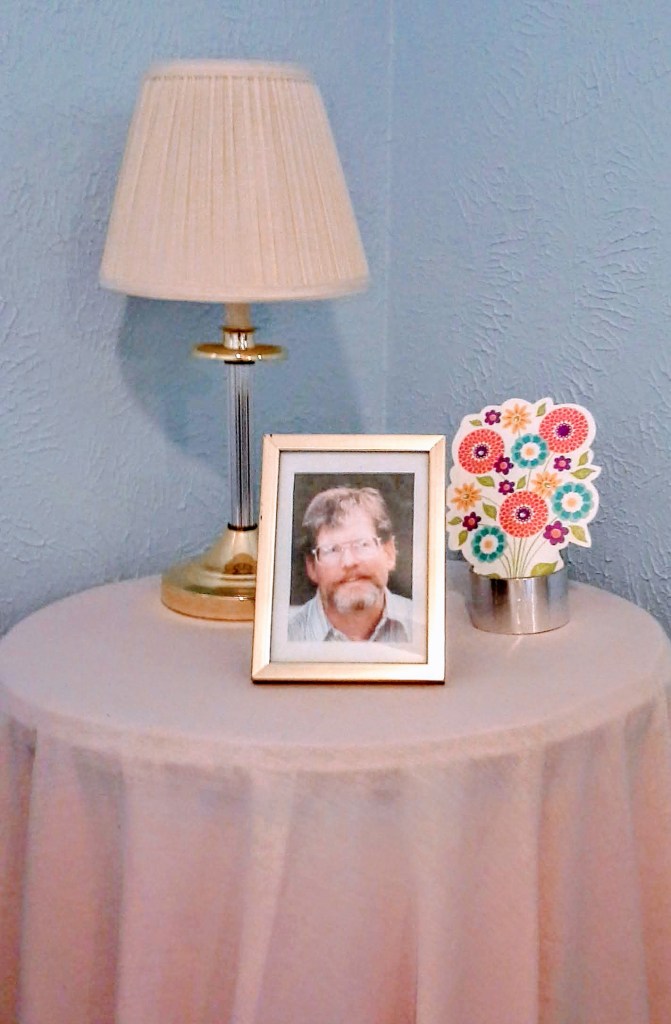

It happens with grief, too. Sometimes a couple isn’t particularly happy, but after one of the partners is deceased, the remaining person looks back and realizes that, despite the disagreements and difficulties, they really had been happy. Or after caring for a loved one during a long illness, the void they leave behind makes those painful days of being with the loved one seem akin to happiness.

Happiness might also be found in anticipation, in hopes for a time when joy might come again. Oftentimes, when someone has gone through a difficult time, they find it easy to look ahead to future happiness, but not when that difficult time is grief for a loved one, and especially not when the loved one is a spouse or soul mate.

The chaos of grief is so great, the blackness so opaque, the pain so all-consuming, that we cannot look to the future as a rosier time. How could there be happiness again when the person we loved more than anything, when the person whose very presence brought us happiness is dead? Chances are there will be happiness again. We change, our perspective changes, our focus changes, so the pain and yearning that once filled our being gradually shrinks into the essence of our souls. We still feel the loss, but like with bark that has broken to allow a tree to grow beyond its confines, our hearts and souls break and then expand to allow other feelings to exist alongside the pain.

Although I often offer a promise of future peace to grievers who show me their pain, I never promise happiness. In fact, I seldom mention the possibility because it’s no consolation. For a long time, the very idea of finding happiness without our deceased mate seems too much of a betrayal of our shared life.

But peace is attainable. Even in the days when the yearning for one more smile or one more word feels as if it will explode out of us, we can find brief moments of peace when the chaos is temporarily stilled, when the roar of pain and loss is temporarily silenced. As time goes on, these moments happen more frequently, and as even more time goes on, the duration of these moments is extended, until one day the peace begins to linger longer than the chaos.

When grievers call out to me in their pain, I want what any caring person wants — to ease their pain. But I, more than most, know that their grief belongs to them. It’s not up to me to take it away from them or even to add to the pain by “bleeding” for them, as people used to tell me they did. (Did they really think it eased my pain to have them bleed for me? That I bared my pain as plea for someone to take the burden of loss from me? If so, they were wrong. Baring my pain was a gift, to show other grievers that they are not the only ones who feel the pain and chaos of grief, that no matter how insane those feeling seemed, they were a normal reaction to an abnormal situation.)

All I can do is offer grievers a place to voice their pain and to send them a wish for (and a belief in) the possibility of peace.

So today, whether you are struggling with grief or trauma, or feelings of unworthiness and guilt for whatever happiness has come your way, I wish you peace.

***

Pat Bertram is the author of Grief: The Inside Story – A Guide to Surviving the Loss of a Loved One. “Grief: The Inside Story is perfect and that is not hyperbole! It is exactly what folk who are grieving need to read.” –Leesa Healy, RN, GDAS GDAT, Emotional/Mental Health Therapist & Educator