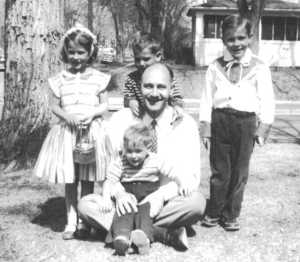

My father, for most of his 97 years, has seemed invincible, as if even death couldn’t defeat him. In fact, I’ve been worried that because of his continued improvement after a recent hospitalization, hospice would evict him. But no one is truly everlasting, and for the first time, I see distinct signs that his long life will someday be ending.

He seems to have reached a new low. He has more troubles breathing, more panic attacks, more nightmares, and more loss of strength — all in the past week. I’ve put off giving him morphine for as long as I could — I’m in and out four days of the week, and I didn’t want him to be alone when he started using the liquid morphine for breathing in case there were side effects. (Jeff, my life mate/soul mate, was on morphine at the end, and he wasn’t himself at all, though it could also have been due to the cancer that had spread to his brain. Oddly, my mother, who died of lung cancer while on hospice, never had to resort to morphine for breathing or for pain.)

I’ll be with my father almost continuously for the next three days, but that’s not enough for him. He wants me here all the time, and I simply cannot do it. It might seem terrible of me to want to continue dancing, but dancing brings me joy, releases whatever stress I might have from being my father’s sole caregiver, gets me out of the house, and keeps me from resenting the situation. (I don’t resent taking care of him, but I would if I had to give up my dance classes.) I’m only gone for a total of about twenty-five hours a week, either taking classes or running errands, and the rest of the time I am here alone with him.

I’ll be with my father almost continuously for the next three days, but that’s not enough for him. He wants me here all the time, and I simply cannot do it. It might seem terrible of me to want to continue dancing, but dancing brings me joy, releases whatever stress I might have from being my father’s sole caregiver, gets me out of the house, and keeps me from resenting the situation. (I don’t resent taking care of him, but I would if I had to give up my dance classes.) I’m only gone for a total of about twenty-five hours a week, either taking classes or running errands, and the rest of the time I am here alone with him.

He could be to the point where he can’t be left alone at all. Luckily, I have a sister waiting to be summoned back to help. It’s hard sharing such close quarters with a strong-willed woman, so I’ve been dragging my feet on making that decision. But I gave in to the morphine, and I will give in to this, too. I need to keep my mind on the goals — my dancing (first!) and my father’s care. Even if I didn’t have dancing, I couldn’t be at his beck and call for twenty-four hours a day. It is simply too stressful. I know people do it because they have no other choice, but I’ve already put in my time when Jeff was dying, and anyway, he was easy to deal with because he knew what was happening to him, and he accepted it. My father, on the other hand, fights the inevitable every step of the way, hurrying through what he calls his “chores” (taking his pills, doing his breathing treatment, urinating) so he can sleep, then hurrying through his naps so he can do his chores, as if he were trying to stay one step ahead of death.

I try to be conciliatory toward his drama attacks (everything he experiences is the worst thing he ever felt in his life, even if it is a short-lived pain or bloody nose or bad dream). But the truth is, it’s hard to find the tragedy in the dying of a 97-year-old man who lived a charmed and healthy life well into his nineties. (I know comparisons are not fair, but I keep thinking of Jeff who led a painful life and died when he was only 63.) But so many years of good health and good living have left my control-freak father ill-prepared for losing control of any part of his life, and because of it, he can’t handle even the small things that go wrong.

Do I sound unsympathetic? I’m not. It’s just that it doesn’t help the situation if I get as panicked as he does. Of course, when he’s gone and my life is turned upside down yet again, I might give in to panic. Or not. All of my life’s uncertainty might (at least I hope it might) help me deal with my own end, particularly since I don’t have a devoted daughter to ease my final years.

***

Pat Bertram is the author of the suspense novels Light Bringer, More Deaths Than One, A Spark of Heavenly Fire, and Daughter Am I. Bertram is also the author of Grief: The Great Yearning, “an exquisite book, wrenching to read, and at the same time full of profound truths.” Connect with Pat on Google+. Like Pat on Facebook.