Grief seldom visits me anymore, but last night, I couldn’t keep the tears from falling. I thought I’d gone through all the firsts — first Christmas after Jeff died, first birthday, first everything. But there was one first I hadn’t expected.

I’d gone to a women’s club Christmas dinner, and it turns out that husbands were invited. In all the years since Jeff died, although I’ve often been in the company of married women, this was the first time I’ve been in a group with mostly couples. I had no idea that such a first would be a problem. But it was. Since the couples wanted to sit together, I got shunted toward the end of the table, between two husbands, both of whom were faced away from me.

I didn’t know any of the men at the dinner, barely knew the women, didn’t know any of the people they talked about, didn’t understand any of the local issues they discussed, so there I sat . . . alone. Toward the end of the evening, a couple of women made the effort to talk to me, so I was able to keep my tears in check, but as soon as I got home, I started crying.

I thought I was over this part, this feeling out of place in a coupled world. I’ve been spoiled in that most of my new friends are widows (or once were widows). There is no feeling of being a third wheel or fifth wheel or any sort of wheel when I’m with them, so the feeling of being superfluous hit me hard. I’m still feeling sad and unsettled. In a little over three months, it will be ten years that Jeff has been gone. It doesn’t seem possible that I’ve lasted this long. It doesn’t seem possible that I can still feel so bad and for such a silly reason.

I’ve been doing a good job of looking forward instead of back, of not lamenting all I’ve lost, but last night, it was simply too much. I wanted go out into the dark and scream about the unfairness of it all, wanted to wail, “But I didn’t do anything wrong.”

But death doesn’t care about fairness. Death doesn’t care about rightness or wrongness. Death came ten years ago, and sometimes, like last night, I can still feel the cold winds of grief it left behind.

Part of me feels as if I’ve been playing a game, playing house, playing at being sociable, and I was suddenly brought back to the reality of my aloneness. Luckily, there’s nothing I have to do today, so I can find my center again before I once more put on my smile and act as if this life is what I wanted all along.

Don’t get me wrong — it is a good life. But sometimes, oh sometimes, I can’t help but think of all I have lost.

***

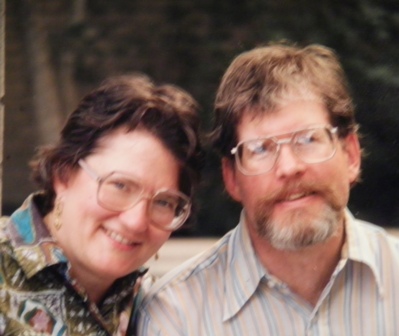

Pat Bertram is the author of Grief: The Inside Story – A Guide to Surviving the Loss of a Loved One. “Grief: The Inside Story is perfect and that is not hyperbole! It is exactly what folk who are grieving need to read.” –Leesa Healy, RN, GDAS GDAT, Emotional/Mental Health Therapist & Educator.

Pat Bertram is the author of Grief: The Inside Story – A Guide to Surviving the Loss of a Loved One. “Grief: The Inside Story is perfect and that is not hyperbole! It is exactly what folk who are grieving need to read.” –Leesa Healy, RN, GDAS GDAT, Emotional/Mental Health Therapist & Educator.