How long must we keep our promises to the dying? Obviously, when we ourselves are dying, those promises will be broken, so does it matter if we break them before we get to that point?

Part of me thinks the promises mean nothing, because after all, the promisees are gone and with it any obligation to them, especially when they bequeathed us such sorrow, but another part of me thinks a promise is meant to be kept.

It’s not a major thing that I’m concerned about. Just a very large coffeetable book. He wasn’t one to make spontaneous purchases, and he seldom spent money on himself for non-essentials, but he saw an ad for this particular book on an inflight magazine and, all out of character, he ordered it. This book was one of the few things he asked me to keep. (Another thing he asked me to keep was a perpetual calendar he’d had since he was a boy, and the rest of the things were items I made that he rescued after I’d thrown them away.) Although it’s not a book I’d ever look at, I have been keeping it, not just because of my promise, but because it reminded me of a different side of him. But now . . . it’s just a very heavy book.

I’m going to have to put my stuff in storage when I leave here, and as big as the book is, it truly is just one thing among many. Still, I have been getting rid of my unnecessities because I don’t want to pay to store a lot of useless things or things I might never need and I almost tossed the book in the bag with the rest of the items I’m getting rid of. But my promise stayed my hand.

So, do promises to the dying have an expiration date? Obviously, if we promise something impossible to pacify them, such as (perhaps) never falling in love again, that promise has no validity. But what about other promises?

***

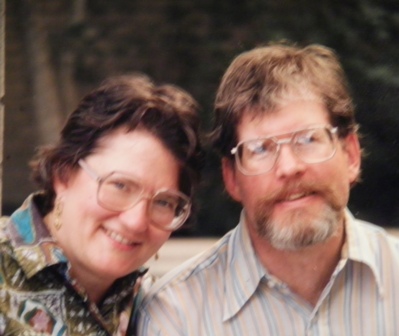

Pat Bertram is the author of the suspense novels Light Bringer, More Deaths Than One, A Spark of Heavenly Fire, and Daughter Am I. Bertram is also the author of Grief: The Great Yearning, “an exquisite book, wrenching to read, and at the same time full of profound truths.” Connect with Pat on Google+. Like Pat on Facebook.