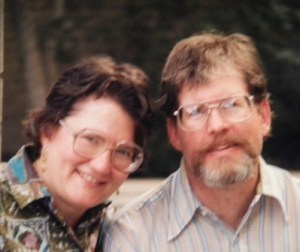

Today is, unexpectedly, a day like any other. So far, on this, the third anniversary of the death of my life mate/soul mate, I’ve experienced no great upsurges of grief, just that perpetual thread of sadness that bastes my life together.

During those first months of grief, my focus was completely on him, on his absence, on the horrendous feeling of goneness that his death left me with. It was as if by thinking of him, by holding him close in my thoughts, by reliving the horror of his final weeks, that somehow I could undo what had happened to him. But the years have taught me what logic didn’t — that he is gone and nothing I do or think or say or hope or pray will bring him back.

During his last days, he became childlike in his needs and actions (as if the combination of the cancer that spread to his brain and the drugs that kept the pain at bay killed the man, leaving only the inner child behind), which confused the issue in my mind. For a long time after his death, I panicked, wondering how he could take care of himself, wishing I could be there to calm his fears and his restless spirit, longing to hold him in my arms and keep him safe.

It’s only recently that the truth hit me. He was an adult, not a child, and except at the end, was more than capable of taking care of himself. Besides, if he does still exist somewhere, he is ageless, timeless, beyond any need of me and my feeble ministrations. (Feeble because nothing I could do erased a single moment of his pain or kept him alive one more day.)

There is an element of blank to my grief — an incomprehension of what it’s all about. I remember how grief feels, though I’m far enough along in the grief process that I have a hard time believing I was that shattered woman so lost in pain. But I don’t know the truth of life and death, and I’m not sure we humans are capable of understanding. And maybe that’s the way it’s supposed to be. It keeps us focused on our lives and not on . . . well, whatever else is out there.

Although time has insulated me from the rawness of my grief, and although my grief work has brought me to the point where I can once again see possibilities and feel hope, there is one thing I will never lose — that great yearning to see him one more time. To hear his voice. See his smile. To hold him tightly as if I would never let him go. But I have let him go. I let him go three years ago, not allowing my needs to bind him to his life of pain.

And I need to let him go now.

Well, here it is — the upsurge in grief I didn’t feel when I started writing this post. Tears are running down my face. I know I need to let him go, to let go of the grief that binds us together still, but not today. Today I will remember. And grieve.

***

Pat Bertram is the author of the suspense novels Light Bringer, More Deaths Than One, A Spark of Heavenly Fire, and Daughter Am I. Bertram is also the author of Grief: The Great Yearning, “an exquisite book, wrenching to read, and at the same time full of profound truths.” All Bertram’s books are published by Second Wind Publishing. Connect with Pat on Google+

![video[7]](https://bertramsblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/video7.jpg?w=240&h=180)